Megatrends 2030: How powerful global forces are shaping the decade ahead

Decisions must be shaped by an understanding and anticipation of what lies ahead. Macroeconomic forces are changing individual, national and regional outlooks. Geostrategic tensions are rising, as are the underlying risks associated with socio-political transition, resource constraints, and climate change. Manufacturers constantly trade off opportunities and risks. But, today, they must also hurdle unprecedented uncertainty and volatility implicit in the impact of these complex issues, known as the world’s megatrends.

In his book Future Shock, Alvin Toffler identified the watershed of a new post-industrial age, pinpointing the enormous structural change afoot in the global economy, and the acceleration of technological advances towards a ‘super-industrial society’ in an information era. Toffler wrote Future Shock 50 years ago, but its prescience continues to strike home, and has resounding relevance for manufacturing organisations today. Manufacturers’ resilience, competitiveness and profitability hinge upon understanding and planning around five vectors of change sweeping the globe.

1. Demographic flux

There will be 8.5 billion people by 2030. Some regions or countries are experiencing an explosive population expansion, priming a huge labour pool and consumer market. Others – notably Japan, Spain and Portugal – are declining. Overall, the fastest-growing age cohort is the older segment: by 2030, over-65s will comprise over a billion people. Seoul, for example, will double its current number of citizens older than 65, who in 2030 will represent 21% of the population of South Korea’s capital.

By then, two-thirds of the world’s population will live in cities, which will generate 80% of global GDP. There will be 43 megacities of 10 million people or more.1 Seventeen of the 20 largest cities will be in currently defined emerging nations; megalopolises such as Mexico City and Sao Paulo, Shenzhen and Shanghai, Mumbai and Lahore, Lagos and Kinshasa will dominate regional economic activity.

By then, two-thirds of the world’s population will live in cities, which will generate 80% of global GDP. There will be 43 megacities of 10 million people or more.1 Seventeen of the 20 largest cities will be in currently defined emerging nations; megalopolises such as Mexico City and Sao Paulo, Shenzhen and Shanghai, Mumbai and Lahore, Lagos and Kinshasa will dominate regional economic activity.

What this means for manufacturers

Elderly people need medications, appropriate lifestyle products, and care. Feasibly, by 2030, robots will increasingly care for the elderly, and medical technology manufacturers will be using additive manufacturing (3D printing) to design and produce efficient aids to serve their needs.

Relevant for packaged food manufacturers is that single-person households will be the fastest-growing household structure in the next decade.

2. Environmental stresses and resource scarcity

Demographic pressures are already straining the planet’s resources, requiring creative solutions around water, food, energy resources, and mobility. The world’s population currently consumes 150% of the earth’s annual renewable resources – a trigger for the past decade’s increasing average annual price volatility of commodities from cotton to coffee, crude oil to corn.

Climate change portends further consequences. Extreme weather events carry the potential for enormous infrastructure damage, and rising seas imperil coastal areas. Biodiversity loss threatens ecosystem sustainability; drought-stricken areas are expanding across the globe; rising temperatures jeopardise agriculture.

But, by 2030, mankind will need 50% more energy, 40% more water, and a third more food than we consume today.2

What this means for manufacturers

Manufacturers must embrace the circular economy not only by reducing waste, but by holistic remanufacturing and materials reusage. Deep innovation is required in food production, sustainable building construction materials, next-level batteries for transport solutions, and energy generation.

Organisations with purpose also match up to mounting consumer expectations around social conscience and corporate ethics.

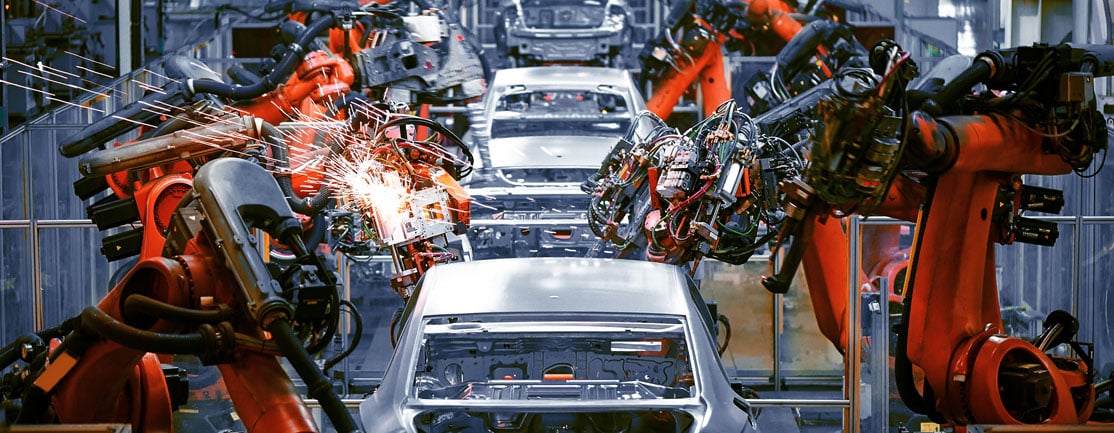

3. Technology rising

The line between man and machine may not yet be blurred. But Japanese roboticist Hiroshi Ishiguro believes that time is not far off. “Already, computers are more powerful than humans in some cases. Technology is just another means of evolution. We are changing the definition of what it is to be human,” he says. As artificial intelligence (AI) leaps forward in deep learning and pattern recognition, some form of man-machine synthesis is stirring.

The line between man and machine may not yet be blurred. But Japanese roboticist Hiroshi Ishiguro believes that time is not far off. “Already, computers are more powerful than humans in some cases. Technology is just another means of evolution. We are changing the definition of what it is to be human,” he says. As artificial intelligence (AI) leaps forward in deep learning and pattern recognition, some form of man-machine synthesis is stirring.

Businesses prioritising this agenda will win. Modelling different take-up rates of AI demonstrates that the forerunner cohort of manufacturers will break even on investments quickest, and generate cumulative cashflow gains of 122% in the decade to 2030, compared with 10% for followers.3 (Adoption laggards should anticipate a significant competitive disadvantage, reflected in negative net cash flows.)

Industry 4.0 will soon transition to 5.0, forging entirely new industries. AI applications and adoption is projected to boost global GDP by between $13-15 trillion by 2030. Manufacturers at the forefront will seize the largest shares of these gains.

What this means for manufacturers

Disruption – powered by technologies and driven by extrapolating consumer choices – is mutating the very nature of ownership. Uber is the world’s largest taxi company but owns no cars; giant retailer Alibaba stocks no inventory, serving instead as broker between buyers and sellers; the most valuable photography company, Instagram, doesn’t make or sell cameras.

Manufacturing-as-a-Service (MaaS) platforms are reshaping supply networks, notably in sectors such as automotive and aerospace. Dutch-based Maas company 3DHubs, for example, enables 200 000 manufacturing deals annually, and claims to “get parts into production in less than five minutes.”

Additive manufacturing may soon revolutionise life sciences. San Diego-based biotech start-up Organovo has run out of R&D funding for its use of 3D printing to ‘patch’ human liver tissue for trials.4 But the pioneering concept may take off in the near future. Facilitating fast-tracking drug research and testing would enable pharmaceutical manufacturers to save major cost (on average, in excess of $1 billion) and time (10-15 years) for new drug development.

4. Rebalancing of economies and markets

Economic forces are re-orientating, from west to east. At some point in the next 20 years, the aggregated GDP of the ‘Emerging-Seven’ (E7) markets of China, Brazil, Indonesia, India, Russia, Mexico and Turkey will overtake that of the established G7.

As much of Asia decouples from an export-led growth path, its middle classes are burgeoning. By 2030, Asia-Pacific will comprise two-thirds of the world’s middle-class population and nearly 60% of middle-class consumption, up from 28% and 23% respectively in 2010. This will be a boon for almost all brand owners and manufacturers, as today’s emerging markets will become the drivers of nearly all consumer goods categories.

This trend will escalate as China’s economy continues its shift towards a consumption-based model, and as the region’s connectivity expands – digitally, in cyber-physical systems, and also in infrastructure such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

What this means for manufacturers

Trade, investment and capital flows are increasingly intra-Asia Pacific, causing the global economy to reshape in multi-polar fashion. In all manufacturing industries, the competitive landscape will change accordingly, and worldwide value networks will need to evolve to upweight presence in Asia-Pacific.

5. New risks

Thirty years ago, political scientist Francis Fukuyama proclaimed the fall of the Berlin Wall as marking “the end of history”. He meant that the hegemony of Western liberal democracy and its related economic order would become universal, heralding stability and wider prosperity.

His prediction was premature. Gini coefficients – the statistical measure of income disparities – are rising across all tiers of nations’ wealth, from low-income countries to high-income ones.5 This escalating inequality is currently manifesting in populism and disaffection, from the ‘Yellow Vest’ movement in France to the rolling street protests in Hong Kong, and the isolationist sentiments of Brexit and ‘America First’.

Populism is linked to protectionist measures. Trade and tariff wars may just be starting. In September, the Trump administration imposed a further 15% tariff hikes on $125 billion worth of imports from China, bringing the average levy on imported goods from that country to 21%. Immediately, China responded by hiking tariffs on over 1 700 US products, including car parts, soybeans, and a 5% levy on US crude oil. The fallout is clear: China’s manufacturing sector slowed for the fourth consecutive month in August, and the tariffs are projected to cost the average American household $970 in the year ahead.

Trade will increasingly be used as a political weapon. Like China and the US, Japan and South Korea are also locked in a tit-for-tat tariff war, rooted in conflict over reparations for Japan’s 1910-1945 colonial rule. Both countries’ GDP forecasts have been trimmed as a result of the dispute.

In October 2019, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) cut its forecast of global trade volume growth by more than half, from its April estimate of 2.6%, to 1.2%. Similarly, forecasts of global GDP expansion are down, from 2.6% to 2.3%. “Beyond their direct effects, trade conflicts heighten uncertainty, which is leading some businesses to delay productivity enhancing investments,” says WTO Director-General Roberto Azevêdo.

What this means for manufacturers

The extent to which trade and tariff barriers may worsen geopolitical and socioeconomic risk is unclear. But it is evident that geopolitics – contextualised with new technologies and population shifts – will present constant risks, and corporate leaders today have to mitigate the new paradigm of volatility.

The repercussions of the megatrends are all-pervasive. Future-proofing for 2030 requires strategic anticipation in five key areas:

- Consider people, first. The current critical skills shortage will worsen. Simultaneously, over a fifth of today’s manufacturing workforce faces displacement by technology. Key question: has the organisation adopted future-focused talent strategies?

- Implement new technologies. Automation and AI, blockchain and big data: these elements of Industry 4.0 have the power to generate major competitive advantage. Key question: is the organisation attuned for the new capabilities of smarter manufacturing?

- Understand changing markets. The challenge involves re-assessing market penetrations and volumes for the world’s rebalancing demographics and socioeconomics. Key question: is the company positioned for the global markets and opportunities of 2030?

- Reboot innovation. Business models will be disrupted by the megatrends. Product offerings must evolve with changing expectations of ever-connected customers. Key question: how does the company re-imagine its products in the age of ‘digital first’?

- Adopt multi-pronged strategies to manage risks. The context of escalating uncertainty and volatility requires visionary yet disciplined leadership. Key question: is a holistic risk and scenario management plan in place to protect all aspects of the supply network?

Conclusion

In the next decade, all industries will face the challenges implicit in the global megatrends. Priorities and decisions made today will affect manufacturers’ resilience and competitiveness in the face of a rapidly changing world.

DOWNLOAD Recovery and resilience: Safeguarding and strengthening the supply chain to thrive through uncertainty for practical strategies to help you safeguard your supply chain and ensure resilience in times of disruption.

1‘The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division

2‘Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds,’ US National Intelligence Council, page iv

3‘Fourth Industrial Revolution: Beacons of Technology and Innovation in Manufacturing’, World Economic Forum, January 2019, figure 2, page 9

4‘https://xconomy.com/san-diego/2019/08/07/organovo-halts-liver-tissue-rd-plans-restructuring-to-cut-costs/

5‘What’s after what’s next? The upside of disruption’, EY, 2018, page 17